Author Interview: Christy Lorio (Cold Comfort)

Learn more about this unique collection of photographs & essays

Several months back, I found Christy on Twitter, read over some of her published essays, and added her to my shortlist of authors I’d like to work with after we got more settled at Belle Point. Then came the recent news of her terminal prognosis, and I wanted to do something to help. We did a little tweaking to the schedule and found room for Cold Comfort, a forthcoming chapbook of all-new essays and original photographs that chronicle Christy’s cancer experience.

For those unfamiliar with Christy’s new diagnosis, Leptomeningeal disease (LMD), it is a very rare condition that develops in only 5 percent of long-term cancer patients; the cancer spreads to the cerebral fluid and there is no cure. At the end of August, Christy learned she likely has six months (or less) to live.

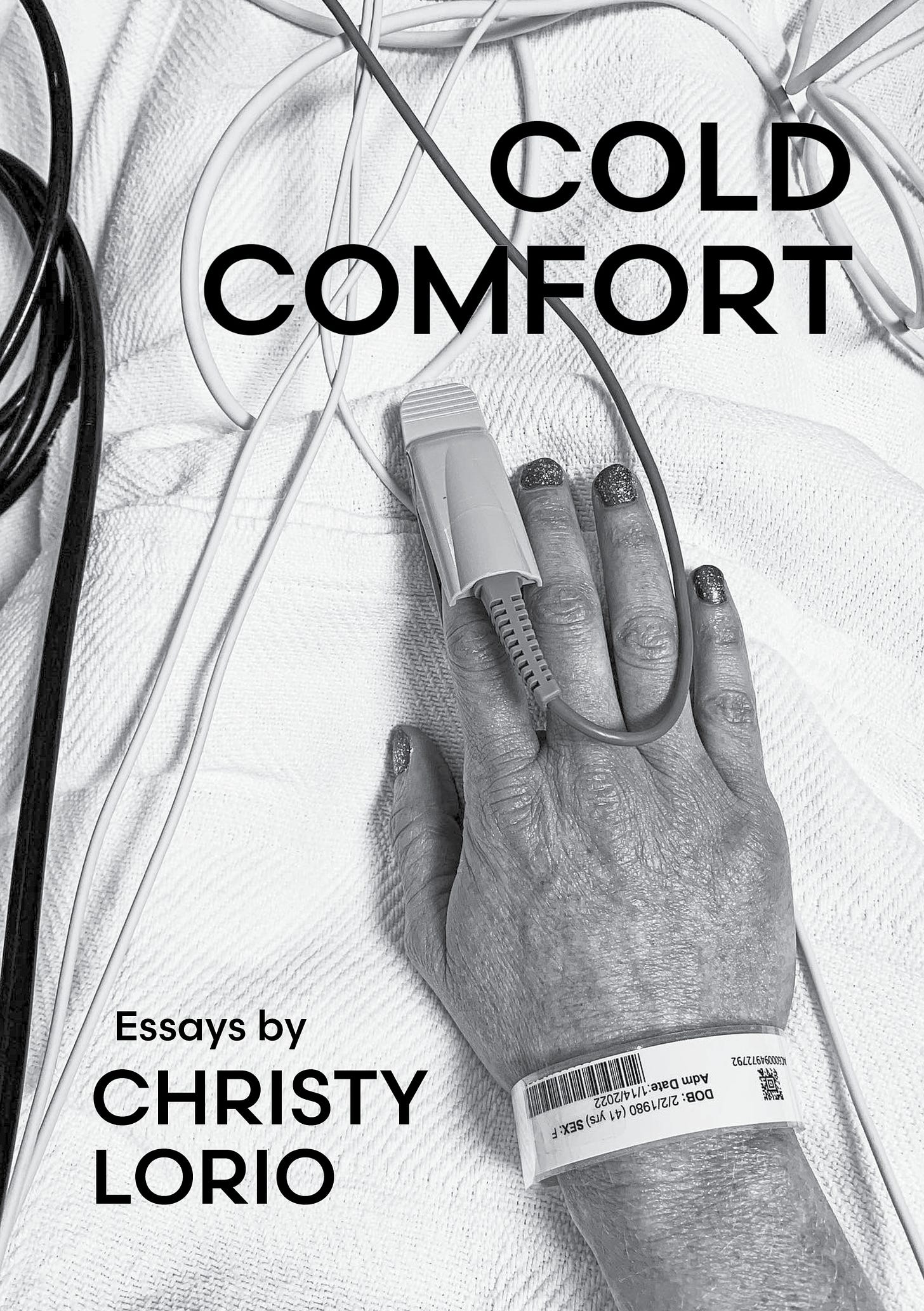

Cold Comfort is a collection of essays and photographs that offers a glimpse into one person’s ongoing experience with cancer: its physical ailments, its lingering effects. In the process, Christy Lorio pulls back the curtain for a visceral perspective of the ways we are constantly tethered to our bodies—as well as how we may hope to live fully within their limits.

In order to help support Christy and her family as they deal with her LMD diagnosis, $5 from every copy sold will go directly to them. So far, thanks to your generosity, we’ve raised nearly $500.

You can pre-order your copy here; we expect to publish November 15, barring printer delays.

Read on for an interview with Christy Lorio.

Casie: First of all, I just want to thank you for trusting us with this project. It has meant a lot to us to be able to bring this together, and I hope that we’ve treated your work with respect and care.

I noticed somewhere that you said all the essays in this collection were new from this year. What made you decide to take that direction instead of compiling work you’d already published in other lit mags, such as the pieces in Scrawl Place, 433, or Barren Magazine?

Christy: Since summer 2018, I’ve been participating in Jami Attenberg’s 1000 Words of Summer. It’s a two-week challenge to write 1000 words a day. I gravitate towards flash, both as a writer and reader, so for this year’s project I decided to write a piece of flash a day. I wanted to write new non-fiction that reflected my current health status in relation to the recent past. Since I wrote all of these in June, I had to revise them to reflect my latest six-month prognosis. Living with cancer is an ever-changing thing.

The photographs are so striking, especially in the black and white format. Could you talk about your process in deciding what to document? Did you see it as an intentional “series” early in your treatment, or did it evolve more organically over time?

I knew that I wanted to combine my writing with photos in book form at some point, and the hospital photos made sense given the subject matter. I started an MFA in Studio Art the fall 2020 semester, where I worked on hospital photos in addition to other bodies of work. I can’t recall the exact moment I started them, but they’ve evolved over the past two years as a way to document cancer treatment as it’s happening. I have a few parameters when it comes to making these. I shoot them entirely on my iPhone so as not to disrupt these medical situations. Introducing a “real” camera into a clinic setting would make healthcare workers nervous due to HIPAA laws. I convert the images to black and white for continuity, and I almost always make the images when no one else is in the room. I try to be as discreet as possible.

What is it like seeing those self-portraits now? Do they signify particularly significant milestones in your treatment? I saw, for example, that you’ll be working on others soon.

I’m constantly making these images, but I rarely go into appointments with the thought, “Today is a great day for a hospital photo.” I’m usually reacting to a new, interesting detail that could make a good still life, or something that is physically happening to me. For example, last fall I went into anaphylactic shock after developing an allergy to a chemo drug. I definitely wasn’t expecting that, so I took a portrait of me hooked up to oxygen in the infusion room. The photos also serve as a way for me to temporarily take myself out of a situation. The camera tends to act as a barrier to what’s happening on the other side of the lens.

Reading through these essays and working through edits with you, I was stunned by the ways in which cancer has pervaded so many aspects of your life. You mention occasionally how people tend to have misconceptions about the daily realities of living with cancer. What do you think people most commonly misunderstand? What would you most like them to understand more clearly?

There are so many challenges, both big and small. Unless a patient loses their hair, you’d have no idea that person sitting next to you has cancer. There are so many little things we take for granted. In my first year of cancer treatment, I was on Oxaliplatin, a chemo that makes you sensitive to cold. I couldn’t drink or eat anything below room temperature, and I couldn’t go into the fridge without wearing an oven mitt to protect my hand. About halfway through treatment, the sensitivity got so bad that I could only drink hot tea. And that’s just one example.

I admire your vulnerability in so many of these essays. What motivates you to share the more embarrassing aspects of your illness?

The only thing that embarrasses me anymore is talking about bowel movements. I usually deflect that with humor or leaving out unsavory details I’m not willing to share. However, in this collection I share quite a bit more than I was willing to share in previous essays, like “So Much Shit.” Telling people you have rectal cancer is pretty demoralizing on its own, but I strongly believe I need to advocate for people to stop being embarrassed about their own bodies and see a doctor when necessary. I’ve had countless people tell me I was the reason they decided to stop putting off getting a colonoscopy.

As many others have observed, it’s amazing to see how much you’ve continued to try and make the most of the time you have left. I hesitate to even phrase this as a question, because—I mean, what the hell else would you do, right? But I’m curious if you have any thoughts about what has enabled you to keep embracing life as fully as you’ve seemed to do.

After I received my six-month prognosis in August, that was the first time I started to slow down. When I was first diagnosed in June 2018, I had just finished my first semester of my Creative Writing MFA. I graduated on time despite cancer and the pandemic, then started my Studio Art MFA the following semester. School gave me purpose. I worked as a graduate and a teaching assistant, respectively, in those programs. Writing and photography kept me sane. They provided me with creative outlets to express what I was going through. What was I going to do, sit at home feeling sorry for myself? Unfortunately, I had to drop out of Studio Art the first week of my last year. It didn’t make sense to pursue a degree I won’t live long enough to finish. I hate that I had to drop, but I’m satisfied with the work I did. I’ve also shifted my mindset. Instead of focusing on my life getting cut short, I’m reflecting on all the things I’ve accomplished thus far. I tend to go nonstop and move on to the next “big win” without giving myself time to appreciate achieving a goal. I’m learning to do that now.

If you’re comfortable sharing, what does treatment look like from here? And how can people show their support?

Unfortunately, there is no cure for LMD. I had full brain radiation to ease symptoms but am forgoing chemotherapy at this time. The chemo is ineffective for most patients and would be directly injected into my brain via a stent. The side effects are brutal. At this point, it’s a quality-of-life issue. I’d rather try to enjoy the time I have left than put faith into a treatment regimen that will make my life worse. For example, my oncologist said I could experience uncontrollable vomiting, nausea, and possible paralysis from the chemo. It’s not worth trying to delay the inevitable when I’ve already suffered so much already.

People can support me by buying Cold Comfort.

You can also join us for a virtual reading with Christy on Wednesday, 11/2, at 7pm Central. Sign up here to get the meeting link in your inbox.

Christy Lorio is a writer and photographer based in New Orleans, Louisiana. In 2021, Christy was a fellow at Arizona State University’s Desert Nights, Rising Stars Writing Conference. Her writing has appeared in Had, 433 Magazine and Oxford American, among other places. Her photography has been seen in publications such as Vice News and In These Times. Her fine art has been shown in galleries both internationally and nationally, including The Ogden Museum of Southern Art and Good Children Gallery in New Orleans. Christy holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of New Orleans.

I've been lucky to be able to call Christy and Thomas friends for a good 19 years. Love you, Thomas. Miss you, Christy.